.png)

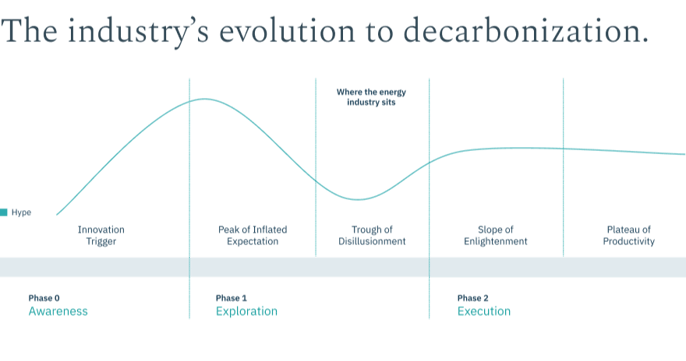

How to approach emissions reductions and carbon markets within the 3 phases of the energy transition

As carbon markets change and new technologies emerge, one of the central questions top of mind for energy companies revolves around planning for tomorrow in light of the dynamic nature of those markets and technologies today.

We see the energy transition playing out in three key phases, each requiring distinct responses to evolving pressures on the industry. As companies take a closer look at decarbonization opportunities, a thorough understanding of emissions data will be essential to agility among the changing dynamics.

Here’s how we view the energy transition and what you need to know about each phase.

Understanding the 3 phases of the energy transition.

We see the energy transition, like many paradigm shifts, occurring in roughly three phases: Awareness (Phase 0), Exploration (Phase 1) and Execution (Phase 2).

Phase 0: Awareness

The period where stakeholders are building alignment on what is important marks the initial phase. Should humanity make net zero a priority? How fast do we need to achieve it? What are we willing to sacrifice in service to net zero and what are we not? Stakeholders inside and outside the industry, representing a range of viewpoints, are engaged in workshops, activism, and lobbying.

A lack of clear standards and uncertainty over the return on investment (ROI) of capital investments renders energy companies without significant incentive to take action during this phase. However, as consensus on the fundamental goals begins to form (e.g affirmations such as progress toward net zero is important) and public pressure builds as a result, companies will be incentivized to start investing in research and “no regrets” options toward likely goals for which public consensus is emerging.

The end of phase zero is marked by consensus that something should, indeed, be done. The days of questioning whether carbon reductions are relevant or necessary winds down and exploration begins.

Phase 1: Exploration

Once sufficient public consensus has emerged around key goals (e.g. net zero, emissions reductions from a sector to achieve a 1.5o scenario) and specific commitments may be tailored to reflect emergent government policy (e.g. regulations, international agreements, etc.), the exploration phase (Phase 1) begins. Phase 1 is the first real step in any large-scale transition and is defined by consensus on an imperative to act, but no specificity or consensus on specific strategies. Government, investor, and market pressures encourage action, but companies are unsure where to begin.

First movers in this stage take on risk because, at this stage, burgeoning mandates and emergent technologies are rapidly evolving. As a result, initial capital investments may not generate the expected ROI and new strategies may produce mixed results. Government policies may signal direction, but details are opaque such that companies are reluctant to invest against them due to unpredictable ROI.

Industry players find that they have incentive to do three things in this phase: develop partnerships, explore opportunities, and advertise their exploratory efforts publicly. There are few ways to directly monetize early action on the open market, so first movers will set up bilateral deals, win over the investor community, and attempt to shape policy. Exploration activities may include operational experimentation with emergent and existing technologies, investments in internal or external R&D projects, lobbying and regulatory advocacy, market research, and investor influence.

Those that prefer to wait for more clarity ahead of significant investment need not lay in limbo. No regrets foundational activities include emissions baselining, forecasting, and scenario modeling. With these foundational investments, companies will be able to perform accurate impact assessments of emissions reduction and decarbonization options, cost, and scale. Furthermore, these activities will ensure that any early actions taken can be accounted for in the future.

In a Phase 1 landscape, companies translate action into shareholder value primarily through the court of public opinion rather than through direct regulatory and financial monetization. Public opinion translates into shareholder value generally through two mechanisms:

- End consumers, especially on the high end of the market, may be willing to pay a premium for products that require lower emissions to produce, whose proceeds support innovation leading to future emissions reduction, and/or that support any of a number of other environmental or social benefits that a company can defensibly claim to provide.

- Investors may be willing to pay a premium for shares in a company that is producing with lower emissions than peers or is investing in R&D to reduce emissions if they believe that this reduces the long-term regulatory risk associated with the company in the future. Investors will be especially inclined to include projections on future regulations into the valuation of long-term infrastructure projects. In some cases, activist investors will take positions in companies that are seen as lagging behind peers on emissions in order to try to realize gains in value associated with improvement.

During this stage, differentiation is the key to creating value. Premium buyers interested in cleaner commodities are only going to pay a premium for perceived leadership in performance, investment, or both. A small number of companies often reap an outsized share of rewards. However, companies run the risk of being perceived as greenwashing if they cannot credibly demonstrate emission reduction claims with defensible and auditable data.

This drive toward differentiation incentivizes companies to claim value in seemingly unique ways, either on performance in one area (e.g. “We produce the lowest emissions gas in a particular basin.”), performance against a unique combination of criteria (e.g. “We are the only low-emissions producer whose workforce comprises >30% veterans.”), or a greater investment in technologies (e.g. “Our GHG emissions claims are supported by continuous monitoring across 95% of our production volumes.”).

Cleaner commodity markets are highly volatile in this stage because value is ascribed by premium buyers based on a combination of forward looking speculation and perceived enhancements in current brand value. Paradoxically, this landscape discourages standardization and promotes differentiation resulting in fragmented strategies and confusion. This creates headwinds with respect to coalescence around a common measurement framework and performance targets on the few parameters that matter most (e.g. GHG emissions).

"Paradoxically, this landscape discourages standardization and promotes differentiation resulting in fragmented strategies and confusion."

The most successful companies in this phase build data management systems in a way that gives them auditability into their carbon tracking methods down to the raw data, while enabling flexibility in reporting to let them keep up with evolving incentives. Tying activities too tightly to a single reporting protocol or certificate is risky, since the market is fragmented and unstable by design. It is also beneficial for companies to gain enough understanding of their operations to assess the impacts of various scenarios on their business and carbon footprint.

The volatility in this phase can benefit regulators, who witness the experimentation on measurement, reduction, and feasibility of performance and reporting. Companies benefit from sharing their learnings with regulators during this phase in order to encourage regulations that recognize and reward early investments.

The end of Phase 1 is the bubble: the combination of the strongest incentives to invest and do something without clarity on what to do creates “invest in anything green” market behavior. Companies do best in this market by monitoring weak signals across the landscape and taking advantage of the capital when it is available, but staying laser focused on what the world will look like in the next phase and adapting for that. Far from being the end of a paradigm shift, most of the enduring value creation and progress occurs after the bubble pops as clarity emerges on what to do and who is leading.

Taking the dot-com bubble as a case study, while many companies did not survive the bust of 2000, much of the enduring value creation from digitization of society occurred after 2000. Several companies founded before the bubble burst (e.g. Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Apple, etc.) survived by focusing on enduring shifts in market dynamics over the hype, and are now some of the world’s most valuable companies. We expect to see the same dynamics repeat in the energy transition.

Disillusionment starts to set in, not only for energy companies, but also investors and stakeholders. The need for order and standardization becomes apparent. At the same time, governments will have had the chance to observe enough experimentation on measurement and abatement to build an understanding on feasibility sufficient to introduce more standardized regulations and incentives. Considering the scale of the problem, a global carbon budget in the tens of gigatons per year, incentives with sufficient scale to drive action requires government action.

Phase 2: Execution

In the final phase, companies have clear mandates for change and can take concrete steps to address them. The industry will know it is in the second phase when companies can make investments in emissions reduction and/or carbon removal that have predictable returns at scale, such as reliance on the US 45Q tax credit for CCS. Coordinated international entities will likely be responsible for the incentives that encourage industry-wide action while ensuring a level playing field. These standards tend to be narrow (e.g. a separate regulation for methane, CO2, etc.), quantitative, and specific. Specificity is required for incentives to work at scale, since it is needed for predictable returns on large-scale investments.

The phase with the most results also comes with the most calm in terms of PR, stakeholder pressure, etc. Once the playing field is level, companies have less incentive to peacock or lobby. They are judged objectively on their results and can get paid at scale for them. Once standards are clear, agreed upon, and baked into government regulations and incentives, the public has confidence that things are being done, and can track the results. As a result, activist pressure tends to lose steam as it is seen as less necessary. For example: SO2 emissions have been reduced nearly 20x in the last 40 years and the proportion of media and environmental activist attention on SO2 has decreased substantially alongside it.

As GHG emissions measurement becomes understood and its impact on the bottom line becomes predictable, we expect to see emissions integrated into core functions the business - GHG measurement integrated into company-wide measurement program, GHG accounting integrated into core financial and production accounting, emissions considerations integrated into operations and commercial decisions along with all the other main considerations. We see this playing out similarly to how sulfur emissions management, backed by clear, predictable, and near universal government regulations and incentives, has integrated into the energy industry and commodities markets. We had this future in mind when we chose to build software and expertise to streamline measurement, reporting, and verification to help companies make the right decisions with real-time insights for operational commodity data and emissions data in the same platform.

Today, industry sits in late Phase 1.

While different segments of the market in different regions have reached different levels of maturity, we would consider the industry to be in Phase 1 in aggregate. There is public and industry consensus that GHG emissions reductions are needed. Voluntary market certificates have emerged, each having different standards and performance metrics. Some have performance on GHG bundled with performance on other environmental and social metrics and a few have GHG performance standing alone. While the U.S. government has not adopted a comprehensive multi-sector framework for GHG management yet, there are many indicators that it is headed in this direction in the medium term. These indicators include spearheading the Global Methane Pledge, the signing of the Inflation Reduction Act, new regulatory requirements implemented or proposed by state and federal agencies, including the SEC.

Additionally, Canada has enacted new regulatory measures over the last year to reduce emissions. In March 2022, the Canadian government released its Emissions Reduction Plan, a sector-by-sector roadmap outlining how the country will cut emissions by 40-45% from 2005 levels by 2030.

The release of Canada's Clean Fuel Regulations in June 2022 also brought into force the Clean Fuel Standards, which are different from a carbon tax model, but still focused on incentivizing the reduction of GHG emissions, with mandates for decreased carbon content in liquid fuels through 2030.

By introducing regulation, governments provide clarity on necessary investments and level the playing field. Government policy requires a balance of competing priorities to be enshrined in regulation (e.g. GHG emissions reduction vs. energy costs, energy security, inflation, geopolitical positioning, etc.). While it is possible that the current geopolitical instability and energy crisis will slow down efforts to reduce GHG emissions, we actually think it will accelerate the progression of the regulatory environment to Phase 2, since voters are more likely to favor clarity and pragmatism over dogma and zeal when both sides of a tradeoff have salience for a given issue. The current state of public consciousness with respect to the balance between economic, energy security, and climate objectives creates an incentive for rational policy making.

How companies should prepare for the next phase with common sense measures.

The emergence of clarity and standardization among markets and regulations on GHG emissions performance marks the beginning of Phase 2. Companies can take steps now to be well positioned to thrive in this environment.

1. Baseline GHG emissions with a measurement-based approach.

The best measurement program is not the one that spares no expense. It is the simplest, cost-effective one that is reliable and defensible. Capital should be deployed sensibly, measuring only what is necessary to ensure rational and impactful reductions, rather than measurement for the sake of measurement. Companies should highgrade their understanding of their own emissions footprint from one that is purely based on generic methodologies to one that is specific to their own assets, utilizing existing data, engineering assessments and modeling, augmenting that with measurement as necessary.

Designing the optimal measurement program requires first assessing the uncertainty in current monitoring and sources of the uncertainty. We recommend that companies conduct relatively simple assessments of uncertainty in their existing measurement program and available technologies upfront before making major investments in monitoring across their operations. Working with companies through this assessment is frequently a first step in our engagements.

2. Identify the most material sources of emissions.

Decarbonizing operations as much as possible will not be a small undertaking. The optimal path requires finding the most carbon that can be abated at the least cost. Optimizing performance will require an understanding of where the most emissions are coming from across operations, both on an aggregate and on a per unit of production basis. Removing information silos between teams focusing on emissions and those focusing on operations makes this easier to accomplish. We had this in mind when we built Operations Hub and Carbon Hub under a common measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) framework. Insights on emission reduction efforts must be integrated with operational outlooks and made easily accessible across teams, enabling companies to chart a clear path forward.

3. Understand the technology landscape.

It is also helpful to have a pulse on the current state of abatement and sequestration technology. This informs the impact and feasibility of potential investments in the near and long term.

4. Understand the market.

Finally, it is helpful to keep a pulse on the incentives available in the market, especially as they will evolve rapidly and inhomogeneously across jurisdictions as we transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2. Companies can take advantage of available incentives if emissions data is managed in a manner that makes it possible to produce defensible reporting with formatting that is flexible enough to conform with requirements in regulatory and voluntary markets that are evolving rapidly.

Learn more about our measurement reconciliation offering. Speak with our experts.

Ian Burgess

Ian is a co-founder and the CTO of Validere. He is an interdisciplinary scientist whose inventions have been recognized with an R&D 100 Award and featured in Scientific American, Chemical & Engineering News, Nature Photonics, and Materials Today. He received a Ph.D. in Applied Physics from Harvard in 2012 and a B.Sc. in Mathematical Physics from the University of Waterloo in 2008.