.png)

Recap of new and potential updates to MRGHG, TIER, and the release of CFR

Timeline of Canada's progress on commitments to climate change.

To understand the state of Canadian regulations for emissions and climate change today, the origin and evolution of policies are important considerations.

In late 2016, the Canadian government finalized the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, a plan that outlined Canada’s commitment to growing the economy while reducing emissions and building resilience to adapt to a changing climate. This plan opened the door for the implementation of both a Canadian clean fuel standard and the federal carbon pricing backstop, which defined the criteria provinces and territories would need to satisfy when choosing to implement their own carbon pricing systems.1

In December 2020, the Government of Canada released its strengthened climate plan, “A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy.” Within this plan, the government proposed to implement annual carbon price increases of $15/tCO2e between 2023 and 2030 and to consider changes that would strengthen federal benchmark criteria. In addition, the first draft of the Clean Fuel Regulations were published for review and commentary.

As part of evaluating the effectiveness of the above measures, at the request of Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), in June 2021, the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices (CICC) conducted an independent assessment of federal, provincial, and territorial carbon pricing systems. The results of that assessment have acted as a catalyst for proposed revisions to the current carbon pricing system, including those provincial systems who had previously received equivalency. After extensive commentary, engagement with key stakeholders, and revisions, the Clean Fuel Regulations were published on July 6, 2022 with a coming into force date of June 21, 2022.

2021 Assessment of Canada’s carbon pricing systems

The assessment identified several trends that undermined the performance of carbon pricing in Canada.

- Opportunities for improved emissions coverage: Emissions coverage was deemed to be 78% of the national total, with jurisdictional emissions coverage ranging from 54 - 87%. Alberta came in at 79% and Saskatchewan at 59%. CICC’s estimated coverage standard indicated 82% of national emissions could be covered under carbon pricing, suggesting room for improvement.

- Differing carbon incentives across Canada: Marginal carbon incentives (the value of an emissions reduction, or the penalty associated with an emission) were found to vary across the country. British Columbia was found to have the highest marginal cost incentive at an average of $47 per tonne for large emitters. Alberta was found to have a marginal cost incentive aligned with the federal carbon price schedule ($40 per tonne in 2021).

- Differing average cost incentives across Canada: Average cost incentives (the cost on emissions owed) were found to vary considerably across jurisdictions, from a low of $4 per tonne to a high of $36 per tonne, with a national average of $17. Alberta and Saskatchewan were found to be below the national average, at $10 and $14 respectively.

- Inconsistent provincial carbon price schedules: The carbon price schedules in all jurisdictions except Quebec are inconsistent with incentivizing continuous improvement over the longer term. Most jurisdictions across Canada have a regulated price schedule out to 2022, while a few have only announced prices to 2021. In most cases, the price schedule is not indexed to inflation and is therefore increasing in stringency at a lower rate than the nominal price would suggest.

- Lack of transparency of cost incentives: Both marginal cost and average cost incentives in large emitter programs often lack transparency with CICC suggesting better transparency on key effectiveness drivers, including allocation, banked credit information, and compliance, is needed to assess the costs and incentives facing large emitters.

CICC’s assessment leading to carbon pricing revisions

In response to the assessment’s key findings and recommendations, the Government of Canada updated the Pan-Canadian Approach to Carbon Pollution Pricing 2023-2030.

Adjustments to the minimum national standards required under the federal benchmark for the 2023-2030 period include:

- Programs must have a carbon price

- Programs must match the minimum federal carbon pricing schedule

- Provinces and territories must maintain the minimum carbon pricing signal

In addition to meeting the annual minimum national carbon pollution price and maintaining a marginal carbon price signal, it requires carbon pollution pricing to apply to an equivalent percentage of GHG emissions from combustion (including stationary combustion emissions, flaring, and on-site transportation emissions) and industrial process emissions.

Increasing stringency of the output-based pricing system (OBPS) will hopefully maintain the carbon price signal, preventing a flood of credits into the market that outweighs demand, creating balance and stabilization.

It also calls out the need for offset credits to be limited to emission reductions that are quantified, verified, and permanent.

Responses by Alberta and Saskatchewan to output-based pricing system (OBPS) updates

Following the federal backstop changes, the governments of Saskatchewan and Alberta proposed changes to their OBPS programs to maintain jurisdiction of carbon pricing within their provinces.

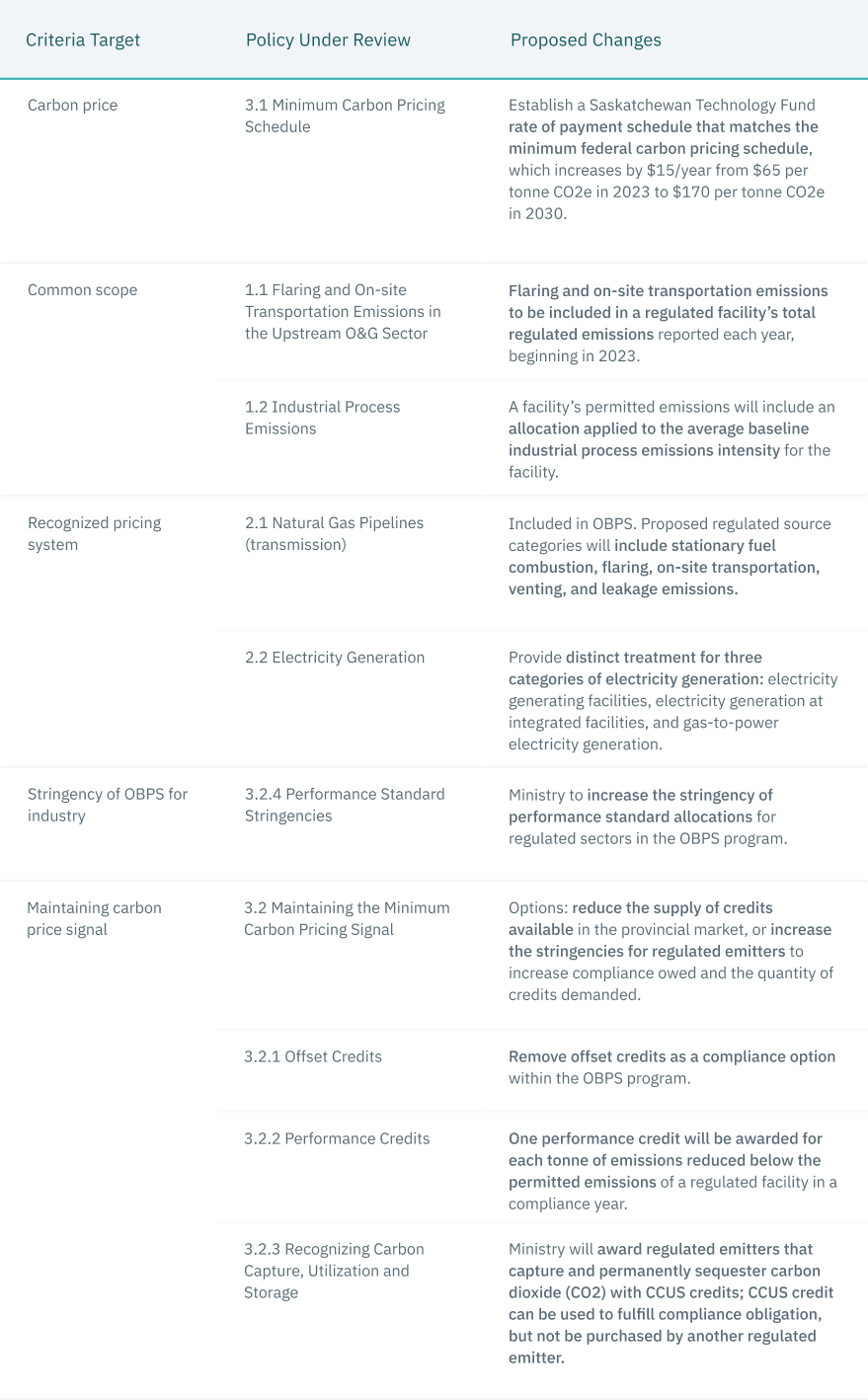

Proposed amendments to SK’s Management and Reduction of Greenhouse Gases (MRGHG) Policy

The proposed changes include aligning the Technology Fund rate of payment schedule with the minimum federal carbon pricing schedule and broadening regulated emission source categories to include industrial process emissions, flaring, and on-site transportation emissions. The government also proposed adding natural gas transmission pipelines and electricity generation to the provincial system.

In addition, Saskatchewan has proposed changes that would increase stringency of performance standard allocations and remove offset credits as a compliance option. Other proposed changes include enabling performance credits to be awarded for each tonne of emissions reduced below permitted emissions and awarding regulated emitters that capture and permanently sequester CO2 with CCUS credits, which could potentially be used to fulfill the regulated emitters compliance obligation.

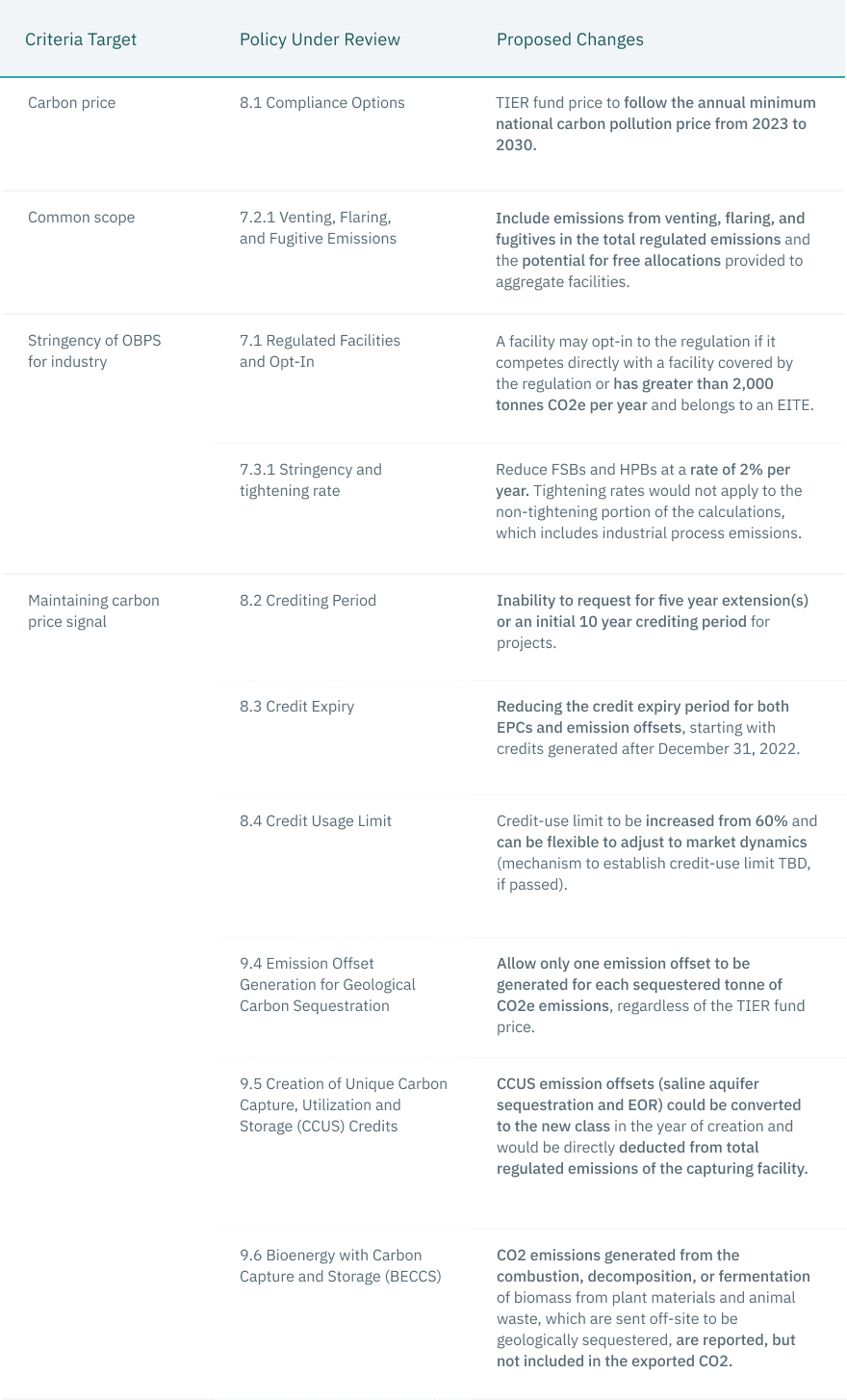

Proposed amendments to AB’s Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction (TIER) Program

Similar to Saskatchewan’s updates, Alberta has proposed aligning the TIER fund price with the annual minimum national carbon pollution price. To address concerns around common scope and stringency, Alberta has also proposed broadening the definition of regulated emissions for the conventional oil and gas sector to include venting, flaring, and fugitives (with the caveat of potential free allocations granted to aggregate facilities). Additionally, the government has proposed reducing the opt-in threshold to enable greater facility and emission coverage, as well as increasing stringency by reducing facility-specific benchmarks and high-performance benchmarks using a linear rate of 2% per year.

Alberta has submitted multiple changes aimed at maintaining the marginal carbon price signal, including removing the ability to extend offset crediting periods, reducing the credit expiry period for performance and offset credits, and increasing the credit usage limit. Similar to Saskatchewan, Alberta wants to address emission offset generation for sequestered carbon dioxide, proposing changes that would allow only one emission offset to be generated for each sequestered tonne of CO2e. This would create a unique CCUS credit that could be directly deducted from total regulated emissions of the capturing facility and, finally, prevent CO2 emissions generated from biomass from being included in exported CO2 emissions.

Additional proposed updates to TIER

Other proposed TIER updates include changes to high-performance benchmarks for electricity, industrial heat, new facilities, and hydrogen; allowing negative emissions allocations; implementing a “call for proposal” process to better align emission offset protocol development and revision with government priorities available resources, and ongoing protocol work; and possible updates to the compliance cost containment program.

Clean Fuel Regulations (CFR) force highlights and (unexpected) changes

The primary goal of the CFR within the overall climate strategy of the Canadian government is to reduce the Carbon Intensity (CI) of the full lifecycle emissions of fuels used in Canada by 15% between now and 2030.2 The reduction obligations apply to primary suppliers who produce or import fuel into Canada. This mainly includes refiners and those parties who import fuels.

Earlier amendments to the proposed CFR framework confirmed that only liquid fuels would be covered by the CFR and exclude natural gas. However, the final release of the CFR went a step further to capture only gasoline and diesel. Other parties are also impacted by the CFR in the credit generation schemes that are available and a necessary component of the available compliance mechanisms.

While the CFR will replace the Renewable Fuel Regulations (RFR) in 2024, volumetric requirements remain the same (5% low CI fuel content for gasoline and 2% for diesel). Participants will report on the CI of their fuels using government established benchmarks for each fuel type and can also expect to see increased reporting requirements over time.

Participation in the credit market

The CFR provides optionality for participants on how to approach reducing the CIof the fuels they produce. Participants can either reduce CI of the fuel they produce or by buying credits generated by others.

The CFR sets out three broad categories of activities that generate credits, as follows:

- Compliance Category 1: Actions that reduce the CI of the fuel lifecycle (e.g. CCUS, on-site renewable electricity)

- Compliance Category 2: Producing or importing low-CI fuel (i.e., fuel with a CI below the applicable CI limit)

- Compliance Category 3: End-use fuel switching in transportation (i.e., switching to electric vehicle)

Activities may be conducted by suppliers themselves or registered creators. A credit clearing mechanism has been established, along with a tracking system for registering and trading credits. The government has also incorporated a maximum price per year for credits, starting at $300/credit to provide increased predictability and certainty.

One material change to the CFR from its initial release, is that for compliance category 1, fuels must be used in Canada to qualify as a credit generating project. This will limit the amount of credits which were initially expected to be generated in this category.

One achievement of the CFR with which carbon tax has yet to find success, is the cross-Canada usability of credits. Credits can be generated anywhere in Canada and used by suppliers who must satisfy CFR compliance obligations. Although the Supreme Court confirmed that Carbon Tax is wholly within the Federal jurisdiction, offsets have not been easily applied across provincial boundaries.

Approaching emissions management holistically

Looking at the evolving regulatory obligations, coupled with the opportunities to engage in compliance based and voluntary markets, requires a holistic approach on the part of participants. Rather than being bound by individual programs, companies need to create an internal system of emissions credits and debits using the most advantageous programs and spending investment dollars accordingly.

The updates to carbon pricing regulations have removed uncertainty around long-term expectations and future marginal cost incentives. The expectation of future carbon prices incentivizes energy companies to invest in low-carbon innovation. Once provincial programs for carbon tax for 2023-2030 are finalized, emitters should be able to confidently assess the financial impacts of carbon pricing, including marginal cost incentives, enabling the uptake of emission abatement technologies that are ready to be deployed. The CFR presents further opportunities to generate credits and manage emissions.

It is important for participants to understand what activities are governed by which regulations as well as have the ability to capitalize on opportunities. This necessarily provokes answers to questions such as:

- Where does program stacking apply?

- Where should I spend my investment dollars?

- How can I strategically balance obligations with opportunities to maximize returns and reduce taxation?

To answer these questions, Validere believes that the initial focus should be on achieving regulatory compliance with a view to expanding to broader strategic initiatives. This begins with a systematic approach: centralizing operations and emissions data; identifying an asset or facility list; inventorying and assigning emission sources to the asset list; calculating emissions utilizing applicable quantification methodologies; following through with necessary reporting obligations; and forecasting and modeling future emissions

A measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) SaaS solution paired with a dedicated team of regulatory experts and advisors allow energy companies to streamline the process to quantify emissions, report efficiently, as well as forecast and model tax obligations and reduction efforts.

1Both Alberta and Saskatchewan have implemented provincial carbon pricing systems and received partial or full equivalency from the Federal government, with a majority of emissions sources falling under these provincial programs and leaving the Federal backstop in place for the remainder.

2 Based on 2016 baseline data.

Corey Wood and Tamar Epstein

Corey Wood is VP, Emissions, Regulatory, and Carbon Strategy, at Validere. He is an industry leader in regulatory compliance for the upstream oil and gas industry. Tamar Epstein serves as Validere’s General Counsel and VP, ESG. She provides expert and strategic legal advice to management, sets internal governance policies, manages the impact of external factors, and ensures legal compliance.